Egyptian mythology, spanning over three millennia, is a complex and fascinating tapestry of tales, beliefs, and rituals that shaped the spiritual and cultural landscape of ancient Egypt. Far more than a collection of fanciful stories, these myths provided explanations for the natural world, justified the social and political order, and offered a profound understanding of life, death, and the cosmos.

At its heart, Egyptian mythology was polytheistic, featuring a vast pantheon of gods and goddesses, each with distinct roles, attributes, and cult centers. These deities often manifested in zoomorphic, anthropomorphic, or theriomorphic forms, reflecting their connection to specific animals or natural phenomena. The ever-present Nile River, the scorching desert, and the predictable cycles of the sun and moon were not merely geographical features but active participants in the divine drama.

The Cosmogonic Narratives: How It All Began

The ancient Egyptians developed several creation myths, often localized to specific cities and their patron deities. However, common threads connect these diverse accounts. The most prominent theme is the emergence of order () from primordial chaos ().

The Heliopolitan Cosmogony:

Centered in Iunu (Heliopolis), this myth posited the self-creation of the sun god Atum, who emerged from the chaotic waters of Nun on a primeval mound. Through masturbation or spitting, Atum engendered Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture). This first divine couple then gave birth to Geb (earth) and Nut (sky), who, in turn, produced Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys. This Ennead (group of nine gods) formed the core of the Heliopolitan pantheon, establishing the fundamental elements of the cosmos and the divine lineage.

The Memphite Cosmogony:

In Memphis, the god Ptah was revered as the ultimate creator. This myth emphasized the intellectual and verbal power of Ptah, who conceived the world in his mind and then spoke it into existence. Ptah was seen as the craftsman god, shaping the universe and all living things through his will and word. This narrative offered a more abstract and philosophical approach to creation.

The Hermopolitan Cosmogony:

In Khmunu (Hermopolis), the Ogdoad, a group of eight primordial deities, represented the chaotic forces of the pre-creation world: Nun and Naunet (primordial water), Heh and Hauhet (infinity), Kek and Kauket (darkness), and Amun and Amaunet (hiddenness or air). These eight deities, through their interaction, brought forth the primeval mound and the sun god, who then began the process of ordered creation.

Key Deities and Their Roles: A Divine Tapestry

The Egyptian pantheon was vast and fluid, with deities often merging or adopting aspects of others. However, some stood out as particularly significant:

Ra (Re):

The preeminent sun god, often depicted with a falcon’s head topped by a sun disk. Ra was the creator and sustainer of life, traversing the sky daily in his solar bark, bringing light and warmth. His journey through the underworld at night represented the cycle of death and rebirth.

Osiris:

The god of the underworld, resurrection, and fertility. Osiris was a benevolent ruler who taught humanity agriculture and civilization. His murder by his jealous brother Set and subsequent resurrection by Isis formed the cornerstone of Egyptian beliefs about death and the afterlife.

Isis:

The great mother goddess, mistress of magic, healing, and funerary rites. Isis was the devoted wife of Osiris and the protective mother of Horus. Her unwavering love and magical prowess enabled Osiris’s resurrection and protected Horus from Set’s machinations.

Horus:

The falcon-headed god, son of Osiris and Isis, and the legitimate heir to the throne. Horus was the embodiment of kingship, representing divine order and justice. His struggle against Set for the throne was a central motif, symbolizing the triumph of good over evil.

Set:

The god of chaos, storms, deserts, and violence. Set was a complex deity, sometimes seen as a necessary force for balance, but more often as the antagonist, particularly in the Osiris myth.

Thoth:

The ibis-headed god of writing, knowledge, magic, and the moon. Thoth was the scribe of the gods, keeper of records, and arbiter of divine disputes.

Hathor:

The cow goddess of love, beauty, music, motherhood, and joy. Hathor was a multifaceted deity, often associated with the sky and the nurturing aspects of the divine.

Anubis:

The jackal-headed god of mummification and the afterlife. Anubis guided the deceased through the underworld and presided over the weighing of the heart ceremony.

The Afterlife: A Journey to Eternity in the Egyptian Mythology

Perhaps no aspect of Egyptian mythology is more renowned than its intricate and optimistic view of the afterlife. Unlike many ancient cultures, the Egyptians believed in a tangible and desirable existence beyond death, provided the deceased underwent proper burial rituals and lived a righteous life ().

The journey to the afterlife was fraught with peril but also offered the promise of eternal bliss in the Field of Reeds, a verdant paradise mirroring earthly existence but free from suffering. Key elements of this journey included:

- Mummification: The elaborate process of preserving the body to house the soul for eternity.

- Funerary Texts: Spells and incantations from texts like the Book of the Dead (properly titled The Chapters of Coming Forth by Day) provided guidance and protection for the deceased’s journey through the underworld.

- The Weighing of the Heart: A crucial judgment scene presided over by Osiris and Anubis. The deceased’s heart was weighed against the feather of Ma’at (truth and justice). If the heart was heavy with sin, it was devoured by Ammit, the “Devourer of the Dead,” leading to a “second death.” If the heart was pure, the deceased was granted eternal life.

Egyptian Mythology in practice: Religion and Society

Egyptian mythology was not merely a collection of stories but the bedrock of their religious practices and societal structure.

- Kingship: The pharaoh was considered a living embodiment of Horus, and upon death, he became Osiris. This divine connection legitimized their rule and reinforced the idea of a divinely ordained monarchy.

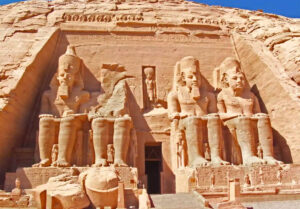

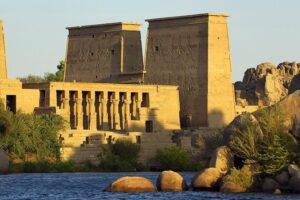

- Temples: Grand temples were built as dwelling places for the gods, where priests performed daily rituals to honor and sustain the deities. These rituals mirrored the cosmic order and ensured the continued prosperity of Egypt.

- Festivals: Religious festivals throughout the year celebrated mythical events, cycles of nature, and the power of the gods, reinforcing community bonds and spiritual devotion.

- Art and Symbolism: Egyptian art is replete with mythological imagery. Hieroglyphs, tomb paintings, and temple reliefs depict gods, goddesses, mythical creatures, and scenes from the afterlife, serving as a constant visual reminder of their beliefs.

The Enduring Legacy

The decline of ancient Egyptian civilization didn’t erase its rich mythology. Instead, elements of its belief system influenced later cultures. This includes Greek and Roman religions. Egyptian mythology continues to resonate in contemporary art, literature, and popular culture.

Its enigmatic gods hold allure. The promise of its eternal afterlife captivates. Profound wisdom is embedded in its narratives. These aspects ensure Egyptian mythology remains a fascinating subject. It offers a window into the spiritual heart of one of history’s greatest civilizations. It stands as a testament to humanity’s enduring quest to understand the universe. This includes our place within it, and the mysteries of life and death.

For the best Egypt Tour Package, contact us, and do not forget to check Egypt’s weather before you go.